Spend 1963 With The Beatles

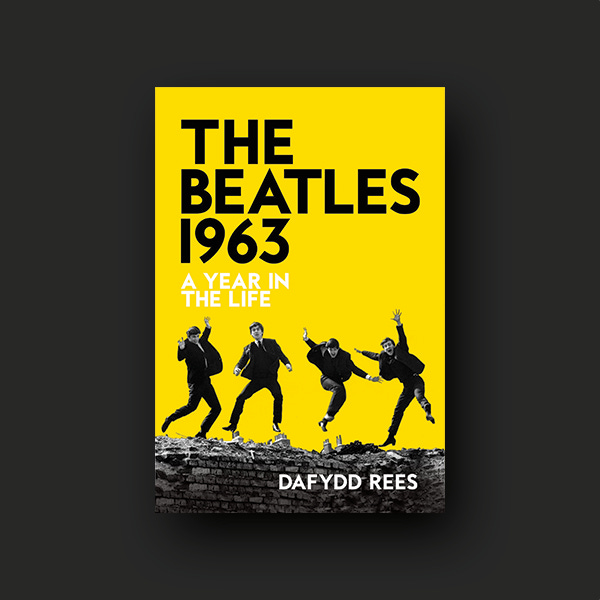

Subscribers will receive two emails per month with 'day in the life' Beatles stories in real time. These stories are expanded extracts from 'The Beatles – 1963' by Dafydd Rees, published by Omnibus Press in October 22.

By subscribing, I agree to Substack’s Terms of Use and acknowledge its Information Collection Notice and Privacy Policy